In 1963, as a free-lance reporter for the Haagse Post, Jan Cremer makes the acquaintance of Frank O'Hara, the poet from New York who had come to the Netherlands in his capacity as curator for the New York Museum of Modern Art in order to install a retrospective exhibition of the work of Franz Kline in the Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum. Cremer shows O'Hara his work, and O'Hara recognises in the paintings a young kindred spirit of Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. Cremer hangs around with O'Hara and takes note of his statements about Kline for the Haagse Post. It is as though what he is hearing is about his own work, '... his forms are strong and simple, the gesture is abrupt and passionate, all the subtleties that he had learned from previous masters with so much fiery zeal were put aside'.

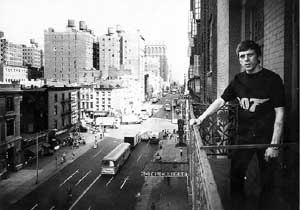

Frank O'Hara (the meanest tongue of New York) and Cremer (described by O'Hara as the terror of Holland) immediately have a good contact. When Cremer arrives in New York in 1964, one of the people that Frank O'Hara takes him to see is Larry Rivers (whom Cremer knew from his Paris period), for whom O'Hara often sat as model in the Fifties. Larry Rivers gives up his studio in the Chelsea Hotel (222 West 23rd Street) for a new working place on Long Island. Cremer appears immediately to have found his first real home: the Chelsea. He gets on right away with the manager of this artist' hotel, Stanley Bard (like Cremer, of Hungarian origin). Jan Cremer would paint for ten years in the Chelsea Hotel, from December 1964 until December 1974 and stay there for a total of 12 years. But just as his work became American during his Amsterdam period after Ibiza, so now it becomes Dutch during his New York period. ('He talks about Holland as only an emigrant could do', wrote Wim Beeren later in Het Hollands Realisme van Jan Cremer 1975).

Concretely, Cremer is inspired by the classic models of Holland: the many postcards sent to him from across the ocean by friends and acquaintances brought him automatically back to the subject of Dutch Landscapes. The tulip fields of the kitschy postcard, every American's image of Holland: tulip fields, windmills, clogs.

Concretely, Cremer is inspired by the classic models of Holland: the many postcards sent to him from across the ocean by friends and acquaintances brought him automatically back to the subject of Dutch Landscapes. The tulip fields of the kitschy postcard, every American's image of Holland: tulip fields, windmills, clogs.

The way that Cremer suddenly hits on depicting tulip fields in New York in 1965 is typical of Pop Art, that is to say, of an art form that harks back to an iconography that is more symbolic than real.

Andy Warhol's Marilyn Monroe has more to do with the projected image of a famous film star than with the representation of an existing person. So too Cremer painted from 1965 onwards large fields of tulips and other aspects of the Dutch Landscape in a way that, as Beeren earlier remarked, is related to the way that Bram Bogart pulls his knife through the porridge of paint, and is related as well to the insatiable desire for broad movement and female themes that we see in the American Dutchman Willem de Kooning. These first Cremer tulip fields are created in the Chelsea Hotel. For the next two decades the Dutch Landscape will become his major source of inspiration, with more and more subjects shooting up on the flat horizon of his memories, all parts of the Dutch decor: polderlands, peat moors, cornfields, farmers' wives. For seven years he will paint cows, falling back on the time when, in the framework of his training at various art academies, he had to visit slaughterhouses and cattle markets in order to make drawings. The battlefields and scenes of war, in which the colour of blood particularly predominated - Cremer's basic colours of red and black - have been replaced by bright, hard tones like those used in the world of American advertising.

("Pop Art was in power in America. I too threw overboard all the 'cultural ballast' and traditional schooling that I had carried with me from the Old World and began a new life with paint. Whereas before I used to paint 'fat' canvasses that sometimes weighed 50 kilos, now I started to paint sparsely and 'thinly'", says Cremer in De Stier van Potter - De Koe van Cremer).

After his informal period, Cremer had landed in a style related to cool Pop Art, but in continuation of his anti-academic, barbaric period, and remembering his experience as a sign painter, he consciously draws in a 'bad' and 'ugly' way. We have to go back a little in time, for what now happens is what Rudi Oxenaar has noted in his introduction to Cremer's retrospective exhibition in The Hague. 'Cremer the painter disappeared behind the facade of the notorious writer, the furious journalist, the libertine scoundrel'.

1963 indicates a turning-point in the manner of painting, but the new subject matter only crops up at the end of 1964 and the beginning of 1965. The year 1964 is completely dominated by the hullaballoo surrounding the success of I Jan Cremer.

It is thus understandable that he doesn't immediately get down to painting. ('Everything that I had dared to imagine in my wildest dreams of America came true, so that for a while I did little painting, overwhelmed as I was by the cacophony of colour and sound of American society', Cremer himself will say). Yet his first place of residence lands him right at the epicentre of modern art in the metropolis of New York: the Chelsea Hotel. Willem de Kooning used to live there, as did the Pop artists Roy Lichtenstein and Claes Oldenburg, as well as the European Nouveaux Réalistes Arman, Daniel Spoerri, Jean Tinguely and Niki de Saint Phalle. In the bar in the basement of the hotel, the El Quichote, Manolo in his red velvet jacket recalls memories of the great drinkers and writers who came to quench their thirst here: Brendan Behan with his incomprehensible but blasphemous Irish brogue, Dylan Thomas with his Welsh songs, Eugene O'Neill. Dating from 1965 are the first photographs in which we see Cremer in his Chelsea studio, with his girlfriend the fashion model Loes Hamel, posing in front of the first of the tulip fields, three or four metres tall paintings in which the tulips, metamorphosed into hearts, perform line dances across the canvas, keeping in ranks as beautifully as the Radio City Music Hall chorus girls.

But Cremer does a lot more than just paint. His turbulent lifestyle brings him more than once to the edge of financial disaster. He has clearly adopted the motto that Jan Cremer Senior often used to use, 'You must keep money moving!'. He works for a living temporarily as editor in chief of the pop music magazine Hullaballoo and as photographer for the girly magazine Nugget, whose editor, Seymour Krim, edited the first anthology of Beat Generation writers and wrote the foreword to the American edition of Ik Jan Cremer, and was in similar financial straits. Jan is far from being a fan of pop music, but his job with Hullaballoo brings him into  contact with that world.

contact with that world.

He lives with the Polish-German model Nico (who later becomes the singer for Andy Warhol's band The Velvet Underground, together with Lou Reed and John Cale) and gets involved in film. In order to learn the ropes of the film profession he spends time - the first three months of each year for four years - in Hollywood, living in a house in Malibu. I Jan Cremer is published in America and straight away gets into the bestseller lists, with a huge edition. He finds a permanent literary agent in the person of Peter Matson who puts his affairs in order. Cremer moves into a large horse ranch in Wellfleet in Cape Cod, a remote domain on a hill between the lake and the sea. It was in the immediate vicinity that Herman Melville wrote 'Moby Dick' and Edward Hopper had his studio, frequently using the region as the subject of his paintings. Cremer's closest neighbours, with houses on the same lake, are Edmund Wilson, who was then living with Mary McCarthy, Dwight MacDonald, the charming ex-Trotskyist who edited the fashionable intellectual men's magazine Esquire in the Fifties and Sixties, and the political journalist Arthur Schlesinger. Other celebrities living in the area, withdrawn into the deep pine woods around the lake, are Tom Wesselmann, who goes fishing every day using his own hand-painted fishes as bait, the widow of the architect Eino Saarinen, Marcel Breuer, the Hungarian designer from the Bauhaus School and the American architect Chermayef. Cremer lives there with Panchita de Peri, of Belgian origin and prima-ballerina with the Harkness Ballet in New York, their daughter Candida Cassandra, his dog Kozak and three horses. For the first year he is more involved with working his land and woods than with creative work. He sits more on the backs of his horses than behind the typewriter. The idea is that Cremer would write in Wellfleet; he still has the studio in the Chelsea for painting. Just as his way of painting undergoes a change in 1963, so there has to come a change in his writing; but this will take a while yet.

Little is known about the low level of painterly activity during this period, except for a few graphic works and photographic documentation. The few works of art, including painted wooden figures - farmers and farmer's wives in traditional Volendammer costume - are snapped up by a small circle of regular collectors.

In 1966 he travels to Paris to work on a series of lithographs, including two Hotdogs, at the studio of Peter Bramsen who mainly works with artists associated with Cobra. The lithographs are a by-product of a project commissioned by a New York advertising agency for a set of billboards, each measuring 12 by 40 metres, to be erected along the highways in America. Cremer extended the project with a maquette for a zeppelin in the form of a Hot Dog with nipples at each end, intended to float above Manhattan, designed Hot Dog Stands, and beds and sofas in a similar form. The maquettes for these were made in the form of collages. In November 1969 he makes a brief trip to the Netherlands to paint a 7 metres wide 'Hotdog' on the hoarding for the first Amsterdamse Drugstore on the Nieuwendijk.

The documentation from 1966 consists of black and white photographs, including those assembled by Gerald Dauphin for Jan Cremer in New York & Jayne Mansfield. (Cremer will spend a large part of that year in South America at the side of Jayne Mansfield, to whom he dedicated his first book. Cremer was seen as the American film star's future husband, and together they visited such countries as Venezuela and Colombia. Back in his New York studio he works further on the theme of Dutch landscapes). The three metres high tulip fields are populated with chaste, faceless women in traditional costume, posing in front of the obligatory windmills on the horizon. Pure cliché, but a cliché that Cremer quickly manages to distil the essence from: he isolates the tulips and paints them as hearts or poppies, vibrating and quivering in light and deep variants of his cherished red. In contrast to the wild, riotous art from the informal period this new work is composed, tempered. It sways gently, breathes silence.

Frank O'Hara dies in 1966 in absurd circumstances - he is run over by the only Landrover belonging to the Rescue Team on the car-free Fire Island! For a homage to his poet and art historian friend Jan Cremer will revert to the more turbulent style, still under the influence of abstract expressionism, of the works that he was making in his native country in 1963 when O'Hara, then curator of the Museum of Modern Art, came to his Amsterdam studio. Due to all sorts of circumstances it takes almost twelve years before this memorial to Frank O'Hara will appear. Titled The New York-Amsterdam Set or The End of the Far West, the portfolio contains ten silkscreen prints and ten poems. In New York in 1965 and 1966 Cremer makes very different work on canvas than what he puts on paper as a writer. The paintings have nothing in common with the roguish mythologization and provocative sexual escapades featured in the writings. And even though Cremer is aware of the market value of such visual material, he introduces few if any erotic themes. He does do it just once, as a provocation, when he uses a Dutch nurse working in a New York hospital as model.

The Belgian sculptor Paul van Hoeydonck, visiting Cremer's New York studio, recalls that Cremer was planning to donate a large painting depicting the current Dutch queen in an erotic pose in the Dutch landscape on the occasion of the marriage of Claus and Beatrix. This historical document, however, was painted over after having been refused as a present.

The Belgian sculptor Paul van Hoeydonck, visiting Cremer's New York studio, recalls that Cremer was planning to donate a large painting depicting the current Dutch queen in an erotic pose in the Dutch landscape on the occasion of the marriage of Claus and Beatrix. This historical document, however, was painted over after having been refused as a present.

In 1967 quite a stir was caused in the Netherlands when Cremer was awarded the Amsterdam Literary Prize. Cremer's third book, Made in U.S.A., is once again written very quickly (on the ranch in Wellfleet) and deals largely with the burgeoning world of open commercial sex in the heart of New York, around Times Square and 42nd Street. Sex at a distance via correspondence, telephone, behind the camera in so-called artist's studios. Only when these reports describe physical contacts, whether fictional or not, do the female models in the book come to life. Cremer is not interested in impersonal sex. The models are also recognisable in his later large nude drawings, lithographs and pastels. He also attacks the craze for impersonal eroticism and sex by means of artificial aids in his theatre plays The Late Late Show and Oklahoma Motel, inspired by American commercials.

On Cape Cod he carved and sawed figures out of driftwood and painted them as nudes and farmers' wives in traditional costume. He made tulip fields with zips. He continued to paint Dutch landscapes populated by ironic nudes and figures derived from comic strips, which would later supply material for the posters and decors for these satirical pieces, put on the stage in the Netherlands and Belgium by Toneelgroep Studio and in German theatres by Theatron Eroticon from Munich, who employed Cremer for a short time as 'artistic director'.

With the temporary move in 1974 to London, his operating base for trips to Lapland, Eastern Siberia and the Altaï mountains in Outer Mongolia, there comes an end to the period as a painter in New York. And another chapter in his life announces itself.

(from: Cremer, Kunstpocket, Kunstforum, Schelderode, 1985)